Bioeconomy Week Scotland 2024 hosted by Industrial Biotechnology Innovation Centre (IBioIC) is taking place between 11 and 15 March 2024.

The Bioeconomy Week is devoted to highlighting biological and sustainable innovations, and their growing contribution to the economy of Scotland. Events throughout the week will focus on sustainable agritech and aquaculture, as well as bio-based materials and processes. The headline event is the 10th anniversary of IBioIC’s annual conference which is based on the theme of transformation – reflecting on the transformation of the sector over the last ten years and looking forward to the transformations that need to happen in the next ten years as we move towards a more sustainable future and full circularity. Innovation will be key to this journey.

In Scotland, a large proportion of innovation in the biotechnology and life sciences sector comes from start-up and spin-out companies. Obtaining effective IP protection for these valuable innovative ideas is not only critical for attracting investment at seed and early stage, but also impacts the long term growth of the company.

A recent joint study by the European Patent Office (EPO) and the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) examined the role of IP rights with regard to attracting funding opportunities and investment (i). A key finding of the joint study is that the biotech sector “is the most intensive user of both patents and trade marks, with close to half of the start-ups in that sector applying for one or both of those IP rights”. Notably 48% of the European biotech start-ups looked at in the study had filed patent applications. Other science and engineering start-ups were unsurprisingly also heavily reliant on patents (with 25% of these start-ups filing patents).

We have taken a look at early stage companies within Scotland’s biotech and life sciences sector which have received significant investment in the past 12 months (ii). Our particular focus has been to assess the intellectual property (IP) held by these companies to evaluate its importance in this context.

Recent Trends and Data

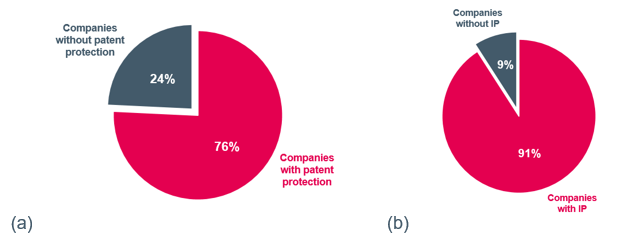

In line with the findings reported in the EPO and EUIPO’s study, the value of IP protection for growth appears to be understood by these early stage companies in Scotland. As shown in Figure 1, around three quarters of early stage companies in the biotech and life sciences sectors who were successful in securing substantial investment in the last 12 months have (or have at least applied for) patent protection. Nearly all of the companies have (or have at least applied for) trade mark protection.

Figure 1 shows proportion of companies receiving substantial investment that have: (a) filed for patent protection; and (b) filed for patent and/or trademark protection

In other words, the vast majority of these companies have at least some form of IP protection in place. It is notable that of those companies who had not filed any patents, a significant proportion of these were food and drink companies (who did not appear to be involved in any R&D). However, in each case, they had filed at least one trade mark. This is consistent with the trends observed in the EPO/EUIPO report which noted that while the traditional food and drinks subsector may not be patent-intensive, they are prolific trade mark filers (given the criticality of protecting their brand).

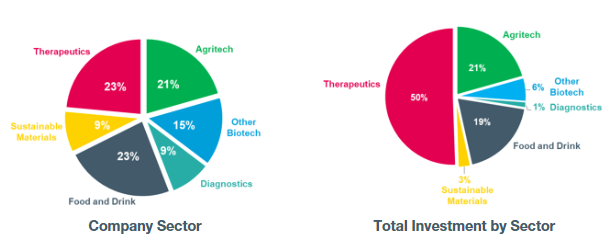

Figure 2 shows the sector breakdown for the companies receiving substantial investment by (a) count; and (b) total investment received.

Therapeutic companies made up only around a quarter of the companies we looked at but they received just under half of the total investment. This was largely underpinned by big deals for Mironid and Chemify, which received amounts of £35 million and £34 million respectively last year. Agritech (which included aquaculture for the purposes of this analysis) and the food and drinks sector also featured heavily – which is not surprising given Scotland’s historic strength and depth in these areas. Within the food and drinks sector, there were at least three companies (Roslin Technologies, Beta Bugs and ENOUGH (3F Bio)) that are working on alternative and more sustainable sources of protein (ENOUGH (3F Bio)) was another one of the big receivers of the year, securing a deal worth £34.2 million.

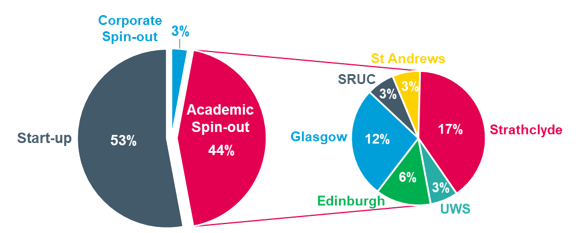

Figure 3 shows the start-up versus spin-out breakdown for companies receiving substantial investment (including a breakdown by source academic institution).

Spin-outs from academic institutions amounted to just under half of the companies we looked at as part of this review. Given that many early stage companies working in biotech and life sciences will be based on lab-made innovation and/or academic research, this is not surprising. The spin-outs came from a wide range of Scottish universities. Within the scope of the cohort of spin-outs looked at in this review, Strathclyde was the top-performer with 40% of the total number of spin-outs coming from that university (constituting 17% of all companies in this review).

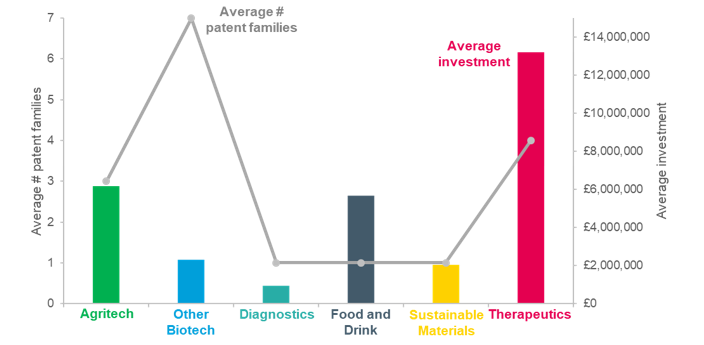

Figure 4 shows a plot of average investment received by companies in each sector, and the corresponding average number of patent families for companies in each sector.

Looking at the average investment awarded to each of the companies in comparison to the average number of patent families held by companies (broken down by subsector), there is a general correlation between the amount of investment and the number of patent families (iii). Again this is not surprising – when seeking higher levels of investment, investors will prefer to see multiple layers of patent protection in place. Reliance on a single patent family will increase the risk – if this patent family should fall, how does the company plan to maintain their monopoly? By contrast, where a company owns several patent families, there are several hurdles for competitors to navigate around – and the risk is lowered for an investor.

On the face of it, the “Other Biotech” category appears to be an outlier. This category includes Penrhos Bio, a 2019 spin-out from Unilever. As stated on their own website, their technology is based on an exclusively licensed “extensive patent library” developed by Unilever over 12 years, comprising 26 families. Therefore, compared to the other spin-outs and start-ups reviewed, this entity appears to be underpinned by a large corporate patent filing strategy. When excluding Penrhos Bio from the data for this category, the average investment for ‘Other Biotech’ is £2.2M, with an average of 2 patent families, which is more in line with the general trend seen in other categories.

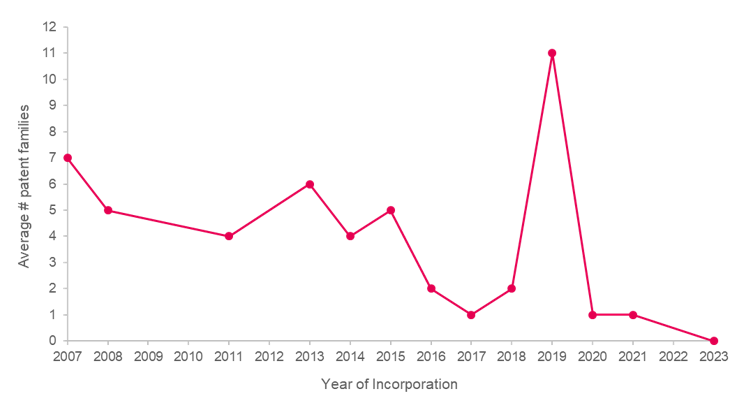

Figure 5 shows year of incorporation versus average number of patent families held by companies incorporated in that year.

Figure 5 shows year of incorporation versus average number of patent families held by companies incorporated in that year.

We also saw a general downward trend indicating that the older companies in the study had filed more patent applications than those which have more recently incorporated (iv). This demonstrates the point that early stage companies looking to obtain investment should look to build a patent portfolio. The older companies appear to have continued to invest in their IP and file for further patent applications as their technology has developed – and this is likely to have contributed to their success when seeking higher levels of investment. For the younger companies which have incorporated in the last two years, it is also worth noting that any patent applications won’t yet have been published. Therefore, these companies might have filed patent applications which aren’t yet accessible to the public.

Conclusions

It can be notoriously difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the intellectual property held by an early stage company. Many such companies are spin-outs from academic institutions or other corporate entities, meaning that the intellectual property might not be registered in the name of the company. Similarly for start-ups, it might be that a founder has filed for IP rights in their own name prior to the formation of a company. In addition, there is an 18 month publication lag for patent applications – meaning that any patenting activity within the last 18 months won’t yet be publicly accessible. In the current review we have attempted to identify the number of patent filings for each entity (looking at the entity itself but also looking for potentially relevant IP based on knowledge of the founders (and likely inventors) from academic institutions and the area of technology) but for all of the reasons noted above we caveat that the analysis should be considered with a degree of caution.

We also appreciate that the current review has not looked at the IP portfolios of early stage companies that have failed to attract further investment. Many of these companies might also have built up robust IP portfolios but still failed to grow: an IP portfolio alone is not a guarantee for success.

Nevertheless it is clear that there is a significant number of Scottish early stage companies receiving substantial investment in the biotech and life sciences sector. The majority of these companies have shown a strong engagement with IP – and as the size of the investment grows, there is a correlation with the volume of IP.

Any investor will take a holistic view of a new opportunity but for an early stage company much of its value will lie in its intellectual property. Therefore young companies should look to devise their IP strategy at an early stage and continually make inward investment to safeguard their IP as their company grows.

- https://link.epo.org/web/publications/studies/en-patents-trade-marks-and-startup-finance-study.pdf

- Early stage companies within the biotech and life sciences sector receiving substantial investment during the period February 2023 to January 2024 as identified by the Young Company Finance Scotland Deals Monitor (34 companies). All companies reviewed had received >£100k in funding.

- ‘Other Biotech’ includes Penrhos Bio, a 2019 spin-out from Unilever. Their technology is based on an exclusively licensed “extensive patent library” developed by Unilever over 12 years, comprising 26 families. When excluding Penrhos Bio from the data, the average investment for ‘Other Biotech’ is £2.2M, with an average of 2 patent families.

- The 2019 average is skewed by Penrhos Bio – when excluding these patent families, the average number is 4.