COVID-19 has put incredible stress on the NHS. Data from NHS England revealed that one year after the onset of the pandemic (March 2021), 24.3% of patients had been waiting for six weeks or more since the date of their referral for one of 15 ‘key’ diagnostic procedures provided by the NHS. Compared to March 2020, this figure represented a 14.1% (March 2021) increase. In March 2021, the vaccine programme was still in its early stages, and the NHS was on the front line fighting the virus. Despite improvements in the prognosis for patients infected with COVID-19 following the vaccination programme, the most recent statistics available at the time of writing (April 2022) suggest challenges in returning to ‘normal’ care remain. As of January 2022, 30% of patients were waiting for six weeks or more for key diagnostic tests, perhaps reflecting the ongoing toll of self-isolating NHS staff and an increasing backlog.

As the UK government brings free, publicly available testing for COVID-19 to an end in England, government statistics indicate that the test and trace programme recorded nearly 500 million COVID-19 tests, over 21 million of whom tested positive. Mass testing of the population was an incredible achievement by our scientific community. This vast undertaking was not only crucial in identifying the infected to prevent the spread of the disease, but in identifying threatening new variants, such as VOC-20DEC-01 (B.1.1.7; ‘UK’ or ‘Kent’ variant) and VOC-21APR-02 (B.1.617.2; ‘Delta Variant’). The infectiousness of the omicron variant of the virus, which emerged in late 2021 is reflected in the data – in November 2021 around 8 million people had tested positive – in the space of 5 months, this figure over doubled to the 21 million referenced above.

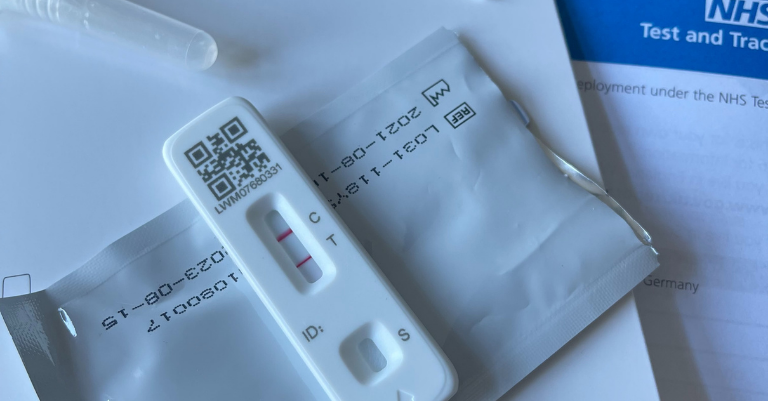

Although mass testing is being wound down, antigen tests and PCR tests will likely remain a feature of our lives going forward, particularly for those wishing to travel abroad, and for those in contact with the clinically vulnerable. Lateral flow tests, now staple household items, were rolled out across the UK as first line of defence against SARS-CoV-2, in the absence of an approved vaccine. The core technologies behind these tests were familiar to the scientific community before the pandemic, but new iterations were devised to meet the sudden demand for quick and cost-effective diagnosis.

Whilst the early stages of the pandemic highlighted the urgent need for innovation in critical care, the fear that the NHS would be overwhelmed by critically ill patients led to the sudden and urgent need to develop quick and reliable means of identifying positive COVID-19 cases. Given times of crisis often correlate with periods of accelerated innovation, it is perhaps unsurprising that the number of patent applications filed at the European Patent Office relating to medical technologies increased by 2.6% in 2020 relative to 2019, and by 0.8% in 2021 relative to 2020.

The roll out of ‘DIY’ at home testing kits for COVID-19 may represent a profound shift in the traditional doctor-led route to diagnosis, with which we are all familiar. COVID-19 tests were not primarily performed by doctors and nurses, but by researchers, technicians, volunteers, the armed forces and individuals. Additionally, these tests were not performed in hospitals and GP surgeries, but in car parks, sports halls, stadia and homes. Furthermore, following collection of a patient sample, these tests could be performed remotely in the absence of the patient, and results were available rapidly. Leaps in DNA amplification and immunology in recent decades has underpinned our ability to roll out mass testing, and has effectively enabled us to map the spread of the virus and its variants around the world in real time. Contrast this to the last ‘great’ influenza pandemic of 1918, when the presence of the influenza virus was only identifiable by severe illness, and it is clear how far our diagnosis capabilities have come.

The success and familiarity of widespread testing will perhaps leave patients with an expectation that ‘point of care’ diagnosis should be just as straightforward when it comes to other pathogens and diseases, not just COVID-19. Small samples of bodily fluids, which require little, if any, medical training to obtain, can be readily used to provide incredibly useful diagnostic information very quickly. From a local point of view, this could be an expectation that cases of mumps or measles in children are identified early, before an outbreak in schools takes hold. From a more global perspective, this could be an expectation that viral and bacterial diseases are sequenced more routinely to identify novel and possibly threatening microbes at an early stage. This public expectation may be reinforced by announcements that the NHS is moving towards adopting a routine blood test capable of detecting up to 50 different cancers1, 2. A widely available test such as this would be welcome, particularly in view of recent reports that up to 340,000 cancer patients face later diagnosis due to NHS staff shortages.

Cancer diagnosis is not the only challenge facing the NHS. With an aging population, patients are presenting with multiple conditions. Overturning historically slow and cost-intensive diagnosis procedures, and improving rapid identification of microbial infections, represents an exciting window of opportunity for companies developing diagnostic products. However, bringing new diagnostic products to market is highly competitive and research-intensive, which can be overwhelming for early stage SMEs. Laboratory costs, clinical trials, regulatory approval, and the long road to obtaining market authorisations can make it feel like bringing the diagnostic product to market remains on the distant horizon.

Having a well-structured IP strategy can make all the difference when it comes to negotiating the long road to market. Securing IP at an early stage opens the door to conversations with collaborators, investors, contractors, manufacturers and suppliers, without having to worry about confidentiality issues. Waiting too long to file for IP protection runs the risk of a competitor devising a similar innovation, and ‘scooping’ IP protection by filing for a patent first. When looking to obtain patent protection for diagnostic devices, it is worth bearing in mind that different scopes of protection may be available in different jurisdictions, depending on the technology. For instance, the scope of protection available for diagnostic devices, which are used directly in conjunction with the patient’s body, may be more limited in Europe compared to the US.

These issues are somewhat less prominent when the diagnostic device employs, for instance, bodily fluids (e.g. lateral flow tests and PCR tests), which can be analysed away from the patient’s body. It is therefore important to seek the advice of an IP professional early in the research & development stage to ensure your market position can be protected in the broadest possible terms. The impact of existing IP protection owned by third parties should also not be overlooked. Existing IP relevant to a particular technology could preclude a diagnostic product being freely brought to market. To open the route to market back up, the SME may find themselves negotiating licences at a very late stage in development, or even being shut out of the market entirely, having already undertaken the hard work to develop a product. It is therefore important to speak to an IP professional to discuss freedom to operate in the market at an early stage of development.

Undoubtedly, the pandemic has permanently altered the fabric of social interaction – whilst some may find the transition back to the old world easy, others will likely continue to wear masks, prefer to dine al fresco, and be conscious of social distancing once the pandemic has passed3-6. Speculations surrounding permanent changes in our behaviour may not be all that surprising when we look at other looming health problems. The emergence of antimicrobial resistance threatens the foundations of modern medicine. Infections that were once treatable, may suddenly become untreatable, with a devastating impact on routine surgery. Tropical diseases that have historically been neglected from a research perspective, or a yet to emerge pathogen capable of cross-species transmission, could open the door to the next global pandemic. Perhaps it is understandable why people are cautious when we peer into what the future may hold. However, the speed with which the scientific and medical communities mobilised resources during the pandemic, and the speed with which multiple vaccines were developed and brought to market (a process that normally takes in the order of years, not months), demonstrates that we have the capabilities to address looming issues now provided there is an appetite to do so.

Without question, intensive research and highly focussed collaboration has led to spectacular achievements in tackling this pandemic. The social and economic shock of the pandemic should galvanise us all into preventing a repeat occurrence, and the infrastructure that has been built to tackle COVID-19 could be used as a springboard to achieving this. Hopefully, with continued research and collaboration at an intensity we are seeing today, health technology companies and institutions will be all the more prepared to lead us out of the next pandemic (hopefully not in any of our lifetimes though).

1 https://www.dana-farber.org/newsroom/news-releases/2020/new-blood-test-can-detect-wide-range-of-cancers--now-available-to-at-risk-individuals-in-clinical-study-at-dana-farber/

2 https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/jun/25/blood-test-that-finds-50-types-of-cancer-is-accurate-enough-to-be-rolled-out

3 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01317-z

4 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-021-00749-2

5 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-56475807

6 https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/jan/10/coronavirus-covid-outdoor-dining-restaurants