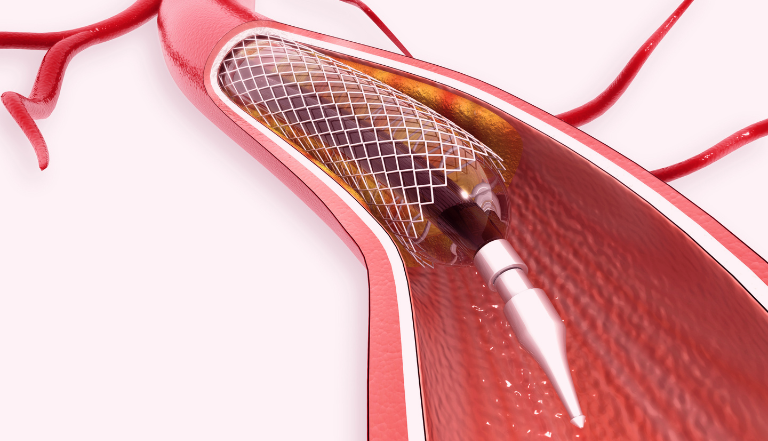

Stents are small, expandable tubes that are used to treat narrowed or weakened vessels (such as arteries) in the body. Although not much to look at, these unassuming tubes are the life-savers behind a multi-billion dollar market, and involve continuous innovation and litigation.

The first patent for a stent was issued in 1972, to Dr Robert Ersek. This patent describes a meshwork metal lattice in combination with an expansion tool (looking remarkably like a caulking gun!) used to deform the lattice and urge it against the walls of the blood vessel. Dr Ersek himself received a stent at the age of 80: “You could even say I saved my own life — 50 years earlier”, he is quoted as saying, by Drexel University’s alumni magazine.

Of course, the stent Dr Ersek received in 2019 would have been far removed from the original version he invented. Moving away from the caulking gun version, the first balloon-expandable stent was developed by Dr Julio Palmaz; the innovation being, as it sounds, to inflate an angioplasty balloon within the stent to expand and fix it within the vessel. The patent was filed in 1985, and issued in 1988; but as Dr Palmaz notes, he had the original concept years earlier, in 1978, and this became critical evidence of his earlier date of conception under the old US first-to-file patent system. The invention was licenced to Johnson & Johnson, and the use of vascular stents approved by the FDA in 1991.

Inevitably, where there is money there is patent litigation. A series of claims and counterclaims of infringement between Johnson & Johnson and Boston Scientific were settled in 2010, with Boston Scientific agreeing to pay $1.7 billion.

Another stent patent dispute, between Edwards Lifesciences and Cook Biotech Inc, led to case law notable to patent attorneys. In the 2009 UK judgment, the court held that Cook’s patent was not entitled to the claimed priority date on the basis that only one of the three inventors was employed by Cook at the time of filing the relevant PCT application. The other two inventors did not formally assign priority rights until after the PCT application had been filed; as such, Cook was not entitled to claim the earlier priority date leading to additional prior art being available to invalidate the patent. This was one of a number of patent cases dealing with the right to claim priority which gave patent attorneys many sleepless nights. However, the EPO’s Enlarged Board of Appeal have recently held that a formal transfer of priority rights may not always be required, and the fact that multiple parties cooperate in filing a patent application may be evidence of an agreement to allow the priority claim to be used. In view of this, it is likely that the Cook decision would be different if heard today.

Other innovations in the field of stents include the use of memory metal such as nitinol to form self-expanding stents which do not require balloons for inflation; and drug-eluting stents, which release drugs to reduce or prevent restenosis. Giving judgment in Conor Medsystems Incorporated v Angiotech Pharmaceuticals Incorporated, the UK House of Lords held that Angiotech’s patent covering, among other things, taxol-coated stents for treating or preventing recurrent stenosis was valid despite containing no data demonstrating that such stents would in fact work. This question has been repeatedly revisited at the EPO, culminating in the recent “plausibility” decision from the Enlarged Board. Litigation regarding drug-eluting stents continues, as, earlier in 2023, Boston Scientific was held to infringe a patent obtained by University of Texas, with costs of $42m.

Naturally, as innovation in this field continues, so will questions of patentability and infringement. Indeed, bioresorbable 3D printed stents are likely to be the next big thing, and we can no doubt expect continued litigation to keep attorneys awake at night.