Lidl, a discount supermarket with a presence in the UK since 1994, has been successful in an infringement and passing off claim against Tesco, the largest supermarket chain in the UK.

The dispute came before the High Court in 2023 and Lidl was overall successful. Tesco appealed that decision and the Court of Appeal has largely confirmed the lower court’s decision. Tesco will have to cease use of its Clubcard Prices logo (as shown below) which has been used to promote its discounted ‘Clubcard Prices’ scheme since 2020.

The Dispute

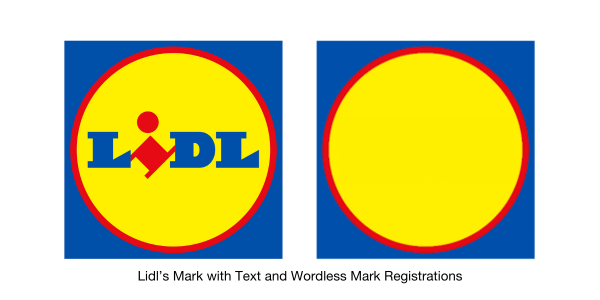

In 2020, Lidl launched legal proceedings against Tesco, claiming that Tesco had infringed its trade marks (the ‘Mark with Text’ and the ‘Wordless Mark’), committed passing off and infringed Lidl’s copyright in the Mark with Text as an artistic work. Tesco counterclaimed that Lidl’s Wordless Mark was applied for in bad faith and therefore was invalid.

Lidl claimed that Tesco had infringed its trade marks through use of a similar sign which calls Lidl and its reputation as a discount supermarket to mind, thereby taking unfair advantage of its reputation. Lidl further claimed that Tesco’s use of the Clubcard sign would be detrimental to the distinctive character of Lidl’s marks, diluting the ability of the marks to identify goods as originating from Lidl and cause consumers to associate Lidl’s marks with discounted prices generally. Lidl also claimed that Tesco had misrepresented that products sold by Tesco shared qualities of products sold by Lidl, including that they were sold at an equivalent price or that Tesco has ‘price-matched’ Lidl. Finally, Lidl claimed that Tesco had infringed its copyright in the Mark with Text, copying a substantial part of the work.

Tesco counterclaimed that Lidl’s Wordless Mark should be invalidated, claiming that Lidl had no genuine intention to use the Wordless Mark and that it was filed as a ‘legal weapon’. Lidl had filed applications for the Wordless Mark on numerous occasions (in 1995, 2002, 2005, 2007, and 2021) which Tesco relied on as evidence of ‘evergreening’ whereby new applications for an identical mark are filed before the earlier mark becomes vulnerable to non-use cancellation.

In 2023, the High Court (HC) held that Tesco’s use of the Clubcard signs infringed Lidl’s earlier trade marks, amounted to passing off and infringed Lidl’s copyright. The HC did find in Tesco’s favour in its claims that certain of Lidl’s earlier Wordless Marks were filed in bad faith as Lidl had failed to substantiate good faith intentions in the 1995 filing and later re-filing of the marks.

Both parties appealed the decision to the Court of Appeal (CA) who issued their Judgement on 19 March 2024. Cases before the CA are heard by three judges. The lead judgment in this case was given by Lord Justice Arnold.

The Appeal

Infringement and passing off

Tesco appealed against the HC’s finding of trade mark infringement and passing off on the basis that the Judge (Mrs Justice Joanna Smith) had erred in her assessment and weighting of parts of Lidl’s evidence. Tesco’s principle argument was that the Judge had erred in finding that the average consumer, on seeing the Clubcard signs, would believe that the prices advertised were price-matched to the equivalent Lidl price. Tesco argued that in the absence of this, there is no basis for a finding of trade mark infringement or passing off. Tesco additionally appealed against the Judge’s conclusions on detriment, unfair advantage and due cause in relation to Lidl’s trade mark infringement claim.

The CA looked at the price-matching allegation first. The main issue was whether the judge was entitled to find that a substantial number of consumers had been led by the Clubcard signs to believe that Tesco’s Clubcard prices were the same or lower than Lidl’s for the equivalent goods. It is important to note that a finding of fact by the HC judge can only be overturned if it is rationally unsupportable.

The CA addressed the evidence that was provided by Lidl and found that the Judge had not erred in her findings, though had perhaps given undue weight to certain evidential submissions. The CA noted that at first, the finding that a substantial number of consumers would be misled by the Clubcard Price signs into believing that the associated prices were price-matched to Lidl may be surprising. However, once you have considered the evidence and the following findings of the Judge, it is less surprising:

• the Wordless Mark was found to be distinctive of Lidl (through longstanding use of the Mark with Text);

• the Clubcard Signs would call Lidl’s Mark with Text to mind; and

• that Lidl has an undisputed reputation for low prices.

The evidence that the judge had based her findings on was then considered.

The Evidence

Lidl submitted three key pieces of evidence in the form of witnesses, the so-called “Lidl Vox Populi”, and a market research survey.

Lidl submitted evidence from two witnesses, Mr Berridge and Mr Paulson, regarding their initial reactions to the Clubcard Sign. Mr Paulson importantly evidenced that he had interpreted the Clubcard Sign as conveying a price matching message. Mr Berridge had visited Tesco’s online store and initially confused the Clubcard Sign for Lidl’s Mark with Text and on further inspection concluded that Tesco was emulating Lidl in offering low prices under the Clubcard Sign (which the CA noted, is not the same as a perception of price-matching).

The Lidl Vox Populi (which translates to ‘voice of the people’) evidenced other consumers’ reactions to the Clubcard Sign. The evidence supported Lidl’s argument that the Clubcard Signs and Lidl’s Mark with Text were similar and that the Clubcard Sign established a link in the mind of the average consumer to Lidl’s mark and Lidl’s reputation as a discount supermarket. It is important to note, that it was not necessary for Lidl to establish that a consumer would be confused as to the origin of products, but that a link was created resulting in Tesco unfairly taking advantage of Lidl’s reputation as a discount supermarket.

Lidl additionally relied on survey evidence in the form of a market research survey commissioned by Tesco. The survey asked consumers numerous questions relating to the new Clubcard Sign. Whilst consumers were primed to answer Tesco, numerous consumers mentioned Lidl and price comparisons when asked about the Clubcard Sign. The Judge found the survey to be qualitatively (but not quantitatively) significant in that some consumers did appear to associate the Clubcard Sign with Lidl. The CA found that the Judge was correct in her judgement of the survey evidence, using it to gauge the perception of consumers but not using it determinatively.

Tesco argued that the Judge should not have given these strands of evidence the weighting she did and that this evidence could not be representative of the average consumer or statistically significant. The CA did not accept this, stating that given Tesco did not contend that the evidence was inadmissible or irrelevant it would have been an error for the Judge to ignore the evidence at hand. The Judge was therefore found to be correct in her thorough evaluation of the evidence and correct in her finding that Tesco’s use of the Clubcard Sign was conveying a price-matching message.

Tesco’s appeal against the finding of passing off was resultantly dismissed. The CA then turned to the outstanding issues on the trade mark infringement case – unfair advantage, detriment and due cause. With respect to unfair advantage and detriment, Tesco challenged the Judge’s findings that there had been change to the economic behaviour of consumers. The CA found that as the price-matching allegation had been upheld, the finding of a change in economic behaviour was rationally supportable.

Turning to the question of “due cause”, Tesco argued that the Judge had erred in law and principle and applied an incorrect test in assessing whether Tesco had used the Clubcard sign with due cause. The CA did not accept Tesco’s argument and found that the Judge was correct in her understanding; it is not enough for a sign to be innocently adopted, there must be more to justify the signs use despite injury to the reputable trade mark. In this case, Tesco was found to have no other justification for its use of the Clubcard Sign and as such, the Judge’s decision that use of Tesco’s Clubcard Sign was without due cause was upheld.

Tesco’s appeal against the finding of trade mark infringement based on detriment to the distinct character of the Mark without Text was resultantly dismissed.

The invalidity of Lidl’s Wordless Mark Registrations

Lidl appealed the Judge’s findings that its wordless registrations (1995, 2002, 2005, and 2007) were applied for in bad faith on numerous grounds. In reviewing the judgment, the CA emphasised that the evidential burden shifts to the applicant where the circumstances relied on by a party challenging invalidity give rise to a prima facie case of bad faith.

Tesco had argued that Lidl had never used nor intended to use the Wordless Mark in the form it was registered and that it should be inferred that the application to register was for defensive purposes (or for use as a ‘legal weapon’) and not for the purpose of functioning as an indicator of origin. These propositions were admitted and as a result, the Judge was correct in finding that the evidential burden shifted to Lidl to rationalise its intentions in making the applications.

The CA held that the Judge was correct in concluding that Lidl had failed to prove that the Wordless Marks had been applied for in good faith. Of note, the Judge was correct in finding that use of the Wordless Mark as a component of the Mark with Text did not establish Lidl’s good intentions for its initial 1995 application and evidence as to the reputation of the Wordless Mark in 1995 (which could have supported its case) was lacking. In addition, Lidl had failed to rebut the argument that its 2002, 2005, and 2007 applications had been made for purely defensive purposes.

Lidl’s appeal against the Judge’s finding that the 1995, 2002, 2005, and 2007 registrations were applied for in bad faith was dismissed.

Tesco’s appeal against the finding of copyright infringement

Tesco appealed against the finding of copyright infringement on the grounds that no copyright subsisted in the work (Lidl’s Mark with Text) and that if the work was found to be original (and copyright subsisted), Tesco had not reproduced a substantial part.

The CA held that the work was original because although the degree of creativity involved in the creation of the work was low there was some creative freedom. However, the scope of protection conferred by the copyright in this case was narrow. Tesco had copied the concept of a yellow circle within a blue square but nothing further. In conclusion, Tesco’s appeal was successful and Tesco were found not to have infringed Lidl’s copyright.

Conclusion

It is common for only one of the CA judges to give a judgment and the remaining two judges to simply state that they agree with the decision of the lead judge. However, in this case, both of the other judges whilst agreeing with the judgment of Lord Justice Arnold, made substantive additional comments. It is clear from these comments that the judges considered this a difficult case on trade mark infringement with Lord Justice Lewison commenting that he “found the trade mark claim and the passing off claim very difficult, at the outer boundaries of trade mark protection and passing off” and Lord Justice Birss commenting on his struggle with the idea that there can be use of a sign which takes unfair advantage of a reputable mark in a way which is with due cause and proposed that current case law has not yet resolved the issue.

As a result of the hearing, Tesco will now have to cease all use of its Clubcard Sign which will purportedly cost them close to £8 million in rebranding. In addition, Tesco will likely have to pay Lidl hefty damages.

This case is an important reminder that consumer and witness evidence must be treated with caution but if it is of a good standard, whilst not determinative, may be given considerable weighting. In this case, Lidl was able to show through its evidence (social media commentary and evidence of shopping habits of consumers) that Tesco’s use of the Clubcard Sign had had an actual impact on consumer’s economic behaviour.