Government bailouts, shrinking GDP and a sudden spike in unemployment as financial pressures mount. No, not the coronavirus crisis that has dominated the first few months of 2020, but the financial crisis of 2008. The banking crisis of that time shaved a total of 6% off GDP in the United Kingdom according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), leading to five successive quarters of economic contraction.

Now, twelve years later, the world faces another calamitous economic crash. This time, however, the crisis isn’t being driven by bad debt, but rather by a virus putting pressure on health systems, spurring drastic economic and social interventions, and leading to personal tragedy for many thousands of people.

As with the last crisis, COVID-19 is causing businesses to experience falling demand, as consumers stay at home and many sectors of the economy find themselves on lockdown. Faced with this uncertainty, businesses large and small are scrambling to find an adequate response. While the current situation is in many ways unprecedented, there are lessons to be learnt from the financial crash.

One of the key questions any business will ask, when under financial pressure and facing an uncertain future, is where can savings be made? When deciding on where to cut costs, the financial crash teaches us that short-term savings need to be balanced against the long-term impact that scaling back might have.

Innovation doesn’t sleep

Innovation is a key area for any business. Business success is predicated upon the ability to innovate and bring better products to market. Regardless of the short, medium and potential long-term economic impacts of coronavirus, what remains true is that the economy of the future will be defined by pioneering technologies such as artificial intelligence, 5G and biotech. What is also true is that these fields move quickly, and the difference between a market-leading company and a company struggling to get a foothold is a question of degree. As such, while scaling down in research and development during a downturn might save money in the short term, it could have a long term impact on overall competitiveness.

While the data around the impact of the 2008 financial crisis on innovation investment is complicated, there is evidence to suggest that those who are willing to continue investing in innovation through a downturn will see long-term gains. This report from the OECD, for instance, highlights the different national approaches to investing during a downturn.

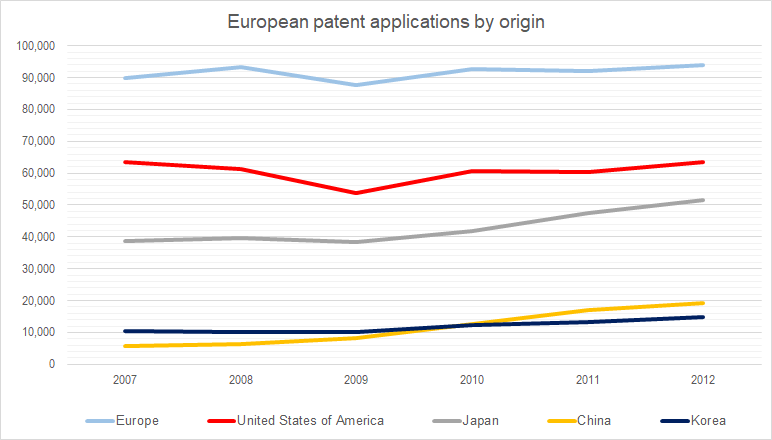

Some countries saw patent filings (a good proxy for R&D spend) fall in the aftermath of 2008 – the US, Germany and the UK, for example. On the other hand, China, Japan and Korea actually saw significant increases in patent filings. While there are clearly wider structural forces at play here – such as the greater exposure of European countries and the US to sub-prime debt and the subsequent ‘credit crunch’ – the post-crash trajectory of patent filing in these countries holds a lesson for businesses.

Statistics from the European Patent Office suggest that China continued to invest in research and development throughout the financial crash, and the number of patents filed by Chinese patent applicants grew by over 200% between 2007 and 2012. The same is true of Japan (34% growth) and Korea (42% growth). The UK, which saw patent filing figures decline following the crash, only saw patent filing numbers recover to pre-crash levels in 2017 – representing nearly a decade of lower than expected levels of investment.

Accepting the presence of all other variables then, it would seem that continued R&D investment throughout the crash of 2008 is a good indicator of continued long term innovation growth. Dropping out of the innovation race doesn’t mean that the race stops, and it could make it more difficult to subsequently catch up.

Another consideration is staffing. Highly skilled companies are only highly skilled because of the staff they have, and another potential consequence of turning off investment during a downturn is the loss of skilled workers. Companies with an IP footprint rely upon skilled scientists and engineers whose talents are very much in demand. If one company decides to reduce its spend on its workforce to manage short-term cash flow, the long-term consequence could be the loss of highly skilled workers to rivals.

As recognised by the OECD report:

“dismissals can lead to permanent “scars” for innovation processes at the concerned firms if laid off employees hold tacit knowledge that is lost to firms as a result.”

There is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to weathering economic turbulence, and the economic impact of the current pandemic will only be understood in the fullness of time. In an increasingly technology-driven economy, however, innovation is central to what many companies do. While it may make short-term sense to cut back on R&D during a downturn, these short term gains need to weighed carefully against the potential long-term costs.