Issues

- Trade mark infringement

- Comparison of logo trade marks, comparison of takeaway and restaurant services

- Assessing reputation

- The ability to rely on honest concurrent use as a defence.

TL;DR:

- A trade mark dispute between high end restaurant located at the Dorchester Hotel in London and a small Chinese take away located 300 miles away.

- After 12 years of coexistence, the infringement proceedings reinforced that actual confusion is not required for a likelihood of confusion to exist and emphasised the importance of due diligence through trade mark searches.

- Despite the relative popularity of the applicant, without evidence of funds spent on advertising, the economic aspect of reputation may not be sufficient when assessing whether unfair advantage has been taken.

- Confirmed that honest concurrent use will rarely be a successful defence to trade mark infringement

The full lowdown

The 2022 decision of the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court in relation to a trade mark dispute between a prestigious Chinese restaurant located at the Dorchester Hotel in London and a local Chinese take away in Barrow-in-Furness (GNAT and Company Limited and China Tang London Limited -vs- West Lake East Limited and Honglu Gu [2022] EWHC 319 (IPEC)) raises a number issues in relation to trade mark infringement that are of continuing interest moving forward.

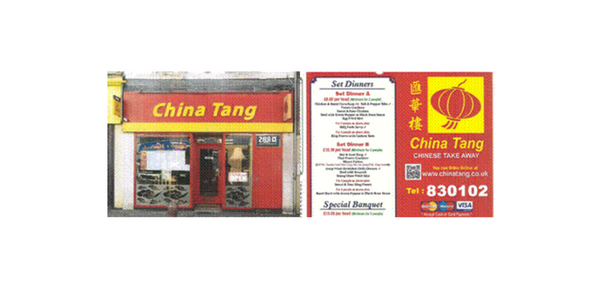

The Claimant had registered the trade mark in question in August 2005; the Defendant had adopted its mark in 2009. Both businesses operated under the same name, “China Tang”, but had adopted different logos:

UK TM No. UK00002415093 as registered by the Claimant:

Vs

Use of the mark by the Applicant - [1]

Comparison of logo trade marks and assessment of a likelihood of confusion

Although the logos were very different in appearance, Judge Hacon found that the dominant distinctive element of the trade marks were the words “China Tang”.

Prior to the trial, the Claimant agreed to remove “self service restaurants” from their registration after a counterclaim for partial revocation by the Defendant. Nevertheless, the court found that even with this amendment, the remaining services, particularly “restaurant services”, were sufficiently similar to “take away services” and that there was a likelihood of confusion. Judge Hacon therefore found that the requirements for infringement were met under s.10(2) of the Trade Marks Act 1994. This decision reinforces that the lack of any evidence of actual confusion on the market has no bearing on the assessment of the likelihood of confusion under s.10(2) – even in circumstances where the takeaway and upscale restaurant are likely to have very different clientele.

Assessing reputation

The Claimant, being a celebrated restaurant in London, also argued that the Defendant took unfair advantage of their reputation in the “China Tang” trade mark under s.10(3). In evaluating reputation in the “China Tang” trade mark, Judge Hacon assessed the evidence before him from both a geographical and economic aspect. The Judge decided that although the geographical aspect was satisfied, the economic one was not. The Judge noted, in particular, that the market share of the Claimant’s restaurant in the UK market as a whole was small. Press coverage and evidence of awards won by the Claimant did not enable the Judge to draw conclusions of the number of individuals who would have been aware of the Claimant’s restaurant. A comparatively modest sum had been spent on marketing the brand, despite the Claimant’s relatively large turnover of £5 - £6 million per year. It is important to note that the Claimant’s evidence did not show how the advertising budget was spent. Judge Hacon also clarified that where the Claimant has a business upmarket from that of the defendant, the fact that a link is made in the mind of the consumer between the two businesses will not necessarily mean that unfair advantage has been taken without further evidence to prove this. Evidence must be provided in support of the suggestion that the reputation of the trade mark is being taken advantage of and in the present case the evidence was not sufficient.

Ability to reply on honest concurrent use use a defence

For its part, the Defendant sought to rely on the defence of “honest concurrent use”. The Defendant claimed that it had been using the trade mark “China Tang” since 2009 without evidence of confusion between the businesses and should therefore be able to continue using the mark. The Defendant argued that they had not been aware of the Claimant’s restaurant when they opened their take-away business. However, the Judge concluded that being a small business did not excuse them from the honest practice of conducting a trade mark or an Internet search before adopting a trade mark for use in commerce. It was put forward that the Defendant would have discovered the Claimant’s business, had they carried out due diligence before using the “China Tang” trade mark. Honest practices would then also have required the Defendant to obtain legal advice regarding their intended trading name. The decision reinforces existing case law in that defendants are unable to argue that they were simply unaware of pre-existing rights held in the trade mark they have been using, and that real honest concurrent use is very rare. Setting up even a small business may require competent legal advice on a variety of matters including the name or marks used to identify the business.

The decision highlights the necessity of seeking experienced professional advice when setting up a new business or expanding an existing business into new commercial avenues, to ensure that you are not inadvertently infringing the rights of a third party.

[1] https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/IPEC/2022/319.html