Marks & Spencer has successfully enforced several UK registered designs against Aldi’s copycat products in a decision that should provide welcome reassurance for designers seeking to use registered designs to protect their products.

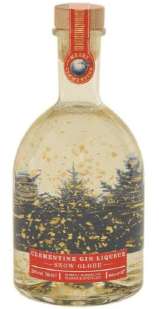

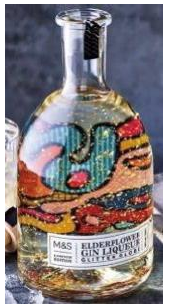

The products in question are Christmas-themed gin bottles. As early as 2019 M&S had been selling Christmas-themed gin bottles containing suspended gold flakes which can be shaken to create a snow-globe like effect under the name “Snow Globe”. Proving to be a popular product, the following summer M&S copied the formula and added a summer twist with the 2020 “Glitter Globe”.

|

|

|

2019 Snow Globe |

2020 Glitter Globe |

Having established a market for gold flake gins, in September 2020, M&S updated the Snow Globe design to include new artwork and a light incorporated within the base of the bottle to illuminate the flakes. Wishing to protect itself, in December 2020 M&S filed a series of design registrations protecting the updated Snow Globe. The first registration claims the bottle simply having the winter artwork applied to its exterior. The second registration additionally claims the suspended gold flakes. The third and fourth registrations claim the bottle with and without the gold flakes taken against a dark background, in which it can be seen that the bottle itself is illuminated from a light source placed in its base.

|

|

|

Registration 1 |

Registration 2 |

|

|

|

Registration 3 |

Registration 4 |

The following Christmas (2021), Aldi launched a range of equivalent products, sold under the name “Infusionist”. Aldi’s products included the same bottle shape, suspended gold flakes and base illumination similar to that used by M&S.

|

|

Aldi “Infusionist” |

Unsurprisingly, and having had some well documented disputes with Aldi in the past. M&S brought proceedings against Aldi for infringement of its registered designs for the 2020 Snow Globe.

In reaching the Court’s decision, the Judge (HH Judge Hacon) construed the scope of protection provided by each of M&S’s design registrations. All four registrations were filed with descriptions stating that the claimed bottles were illuminated, and the Court accepted that such descriptions can in principle be used to construct the scope of protection of the designs. However, interestingly, despite apparently taking the descriptions into consideration, the Court found that only the third and fourth registrations should be considered to claim the illumination, and that the first and second registrations should effectively be considered non-illuminated. Nevertheless, in the end such a distinction did not matter. The Court found that the similarities between M&S’s registrations and Aldi’s Infusionist products we more striking than their differences, and concluded that all four M&S registrations were infringed by the Aldi products complained of.

However, it is notable that the case does not fully consider the effect of the 2019 version of the Snow Globe as prior art against the 2020 registrations. Given that the scope of protection construed by the Court in relation to the first and second registrations excluded the feature of illumination, it is difficult to understand why the Court felt that these two registrations produced a different overall impression from that of the 2019 version of the Snow Globe, particularly where the only differences appear to lie in the specific nature of the applied artwork. It appears that there is a case to be made that at least the first and second registrations may not be valid, and are therefore not infringed. However, this situation could have been avoided entirely if M&S had registered its designs before launching the 2019 Snow Globe, or within 12 months of that launch date since in such circumstances the 2019 Snow Globe would not be citeable prior art.

Moreover, whilst the case in the end did not turn on the presence of illumination sources, M&S’s reliance on the descriptions for establishing the existence of illumination clearly failed with respect to the first and second registrations. This situation might have been avoided if M&S had secured additional registered design protection comprising representations showing the bottle in both illuminated and non-illuminated states, thereby expressly claiming an element of internal lighting as an element of the design. M&S could have complimented this by using a written disclaimer to make clear that the scope of protection claimed did not extend to non-illuminated bottles.

Finally, it is notable that M&S’s representations are based on colour photographs. Whilst the decision did not turn on any elements of colour, had Aldi taken a more cautious approach it may have been possible to avoid infringement by using different coloured artwork, flakes and illumination to that claimed by M&S. Likewise, M&S could have mitigated against this risk by including black and white representations, in which colour is disclaimed. Alternatively, M&S could have included a written disclaimer, disclaiming the colours shown in the representations.

The above notwithstanding, the decision should provide welcome reassurance for designers seeking to use registered designs to protect their products. Product design is, like many creative processes, based upon a series of incremental developments, such as in the case of the Snow Globe. However, this decision shows that it is not necessary to create a brand new product category to obtain enforceable protection, and that protection can successfully be obtained for providing a creative new look and feel to an old product. Nevertheless, the decision also shows the value of obtaining expert advice at an early stage to avoid your own prior disclosures, and the downsides of relying on description elements to address inadequacies in the available representations.

At Marks & Clerk our designs experts are highly experienced in advising clients on matters of industrial design filing strategy across a wide variety of industries. If you have a design and you would like to obtain comprehensive and robust protection, please don’t hesitate to contact us.