The first Test match between England and Australia was played in Melbourne, Australia, in 1877. The ninth Test, played in 1882, saw the famous defeat of England on its home ground at the Oval which ultimately gave rise to the “Ashes”.

But cricket as a game played in England goes back much earlier than this, to 1550 at least, and possibly even to Saxon times. Over time, those interested in the game sought to create improvements, and understandably wished to benefit from these, and this lead inevitably to cricket-related patents.

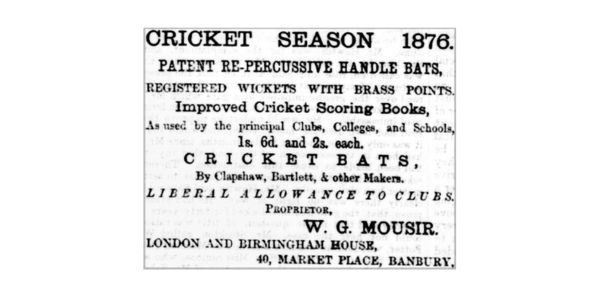

Twenty years before the first Test match, newspapers were advertising patented cricket bats and balls, patented buckle leg guards, “guaranteed to fit any leg size”, and all kinds of patented cricketing accessories. The year before the first Test, my local paper, the Banbury Guardian, carried an advertisement for “patent re-percussive handle bats”, offering a “liberal allowance to clubs”. The Espacenet database contains a multitude of cricket-related patents from 1893 onwards. 1893 alone saw seven patents with “cricket” in the title filed in Great Britain for bats, hand grips, leg guards, bags and even “improvements in apparatus for indicating the score of games such as the Game of Cricket”.

The Espacenet database contains a multitude of cricket-related patents from 1893 onwards. 1893 alone saw seven patents with “cricket” in the title filed in Great Britain for bats, hand grips, leg guards, bags and even “improvements in apparatus for indicating the score of games such as the Game of Cricket”.

As explained in a patent application for a light-weight bat, and its manufacture, filed in 2021 (GB2607869A):

“Innovation within the field of cricket bat design presents a unique set of challenges. Like the game, the equipment is rooted in tradition and the laws that govern both the production processes and material composition of the bat are, as a consequence, strict. These rules are largely set by the Marylebone Cricket Club, MCC. The task therefore is to work within the confines of these rules and yet continue to drive progress in the bat development”.

Despite these apparent restrictions, a quick search of Espacenet (which of course does not include all patents) reveals over a hundred applications with “cricket bat” in the title.

For example, GB2067078, filed in 1980 by cricketers Dennis Lillee and Graeme Monaghan, covers a low-cost, low-maintenance cricket bat with a handle and blade formed from extruded metal, which likely relates to the famous occasion in December 1979 when Dennis Lillee walked out to the crease with an aluminium bat during a Test at Perth.

Also unlikely to strictly conform to MCC rules is the “Smart Cricket Bat” covered by 2019 Indian application 201941017797. This inventive bat includes at least one of an accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer, pressure sensor and microphone, and can track a player’s performance over time and generate a feedback report.

As you might expect, there are also patent applications, such as WO03033081A2, filed by a South African inventor, which cover “smart wickets”, including sensors for determining exactly when a bail is dislodged from its stump, and in this case also comprising an audio or visual indicator that can be used by an umpire. WO2012027776A1, filed by an Australian, provides hollowed out stumps containing cameras that broadcast a three dimensional view.

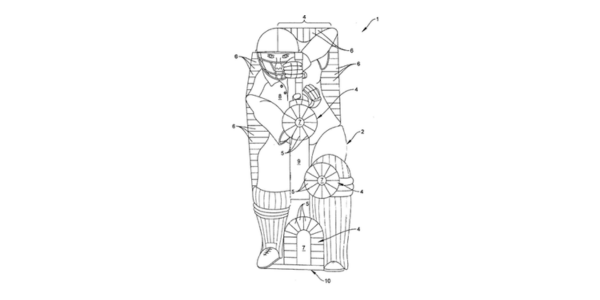

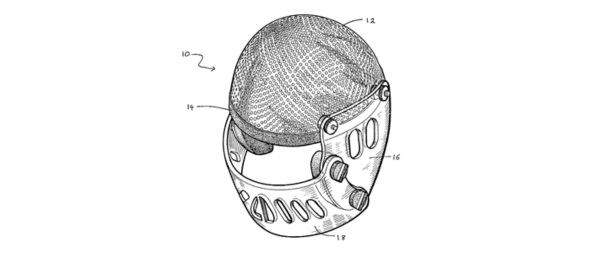

Another area of focus for inventors has been the batsman’s protective helmet. GB2184934A, filed in 1987 by former England cricket captain Michael John Knight “Mike” Smith, provides a metal helmet, illustrated below, which is light-weight, impact-resistant but also provides a flow of cool air over the batter’s head.

Helmets for umpires are also the subject of patent applications. GB2610905A, filed in 2021, provides a helmet that is both a safety device and “an evidence gathering measuring machine” using video capture and microphone.

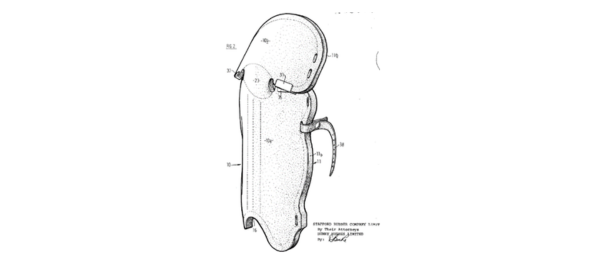

Leg guards too have been a focus for inventors. 1984 New Zealand application NZ205077A provides a leg guard with a flexible knee zone, while GB2407018A, filed in 2005, covers a moulded one-piece three-dimensional shaped pad which includes a high density foamed plastic material, including an air cavity, shown below.

Of course, inventors have also sought to improve the game of cricket through application of the latest technologies. WO2021124351A1 filed in 2021 discloses a cricket umpiring system (an “umpire bot”) that includes an AI module to train the system, and facilitate real time decision making based on analysis of player profile and contextual information. WO2021178755A1 covers a virtual reality environment, configured for use in a cricket simulation, where the projectile is a cricket ball and the player in the live-action sequence is a bowler in a cricket match.

Patents inspired by the ancient and ever-popular game of cricket, covering every aspect of technology from sensors and software, to materials and manufacturing, are a fine example of how patent protection can encourage innovation, and that invention and investment may be rewarded.

Sadly, a search of the Espacenet database does not reveal any patents covering “a method for preventing a batting collapse”, although perhaps the “Practice Apparatus For Use By Persons Wishing To Improve Their Ability To Play Cricket” of WO2021191573A1, filed in 2021, may prove helpful!