This article was originally published in Managing Intellectual Property and is available at www.managingip.com.

One minute read:

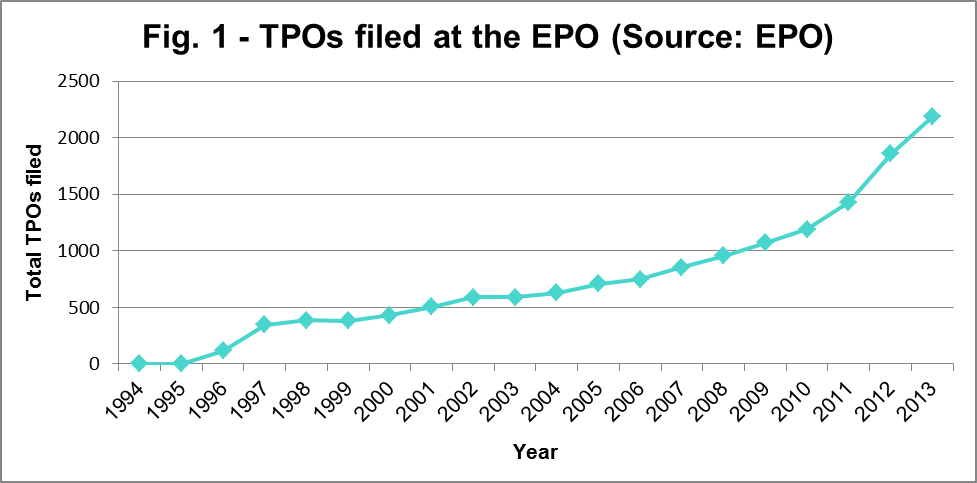

Data from the EPO show that TPOs are increasingly being filed in order to challenge patent applications during examination. Successful outcomes include both the failure of the application to reach grant and amendment of the claims so that they no longer present a problem for the third party. In view of the potential disadvantages of filing TPOs, as well as the fact that different rules and procedures apply at different patent offices, consideration needs to be given on a case-by-case basis as to whether a TPO is the best avenue of challenge. Numbers of observations filed at the EPO have been increasing rapidly, but remain relatively low. Numbers filed against PCTs remain very low. Pharmaceuticals, basic chemicals, medical equipment, special purpose machinery, and measuring instruments are the fields in which the highest number of TPOs are filed.

Businesses would ideally like to be able to pursue their commercial interests in every case without fear of infringing IP rights held by others. However, with patent filings increasing year-on-year, this will often not be the case. Readers will be aware of the consequent importance of performing adequate due diligence and establishing freedom to operate (FTO) prior to commencing any new commercial activity. Typically, part of the due diligence process involves searching for relevant third party intellectual property rights (IPRs) in the area of commercial interest, and analysing these rights for their relevance to the type of business activity in question.

In general, the primary focus of FTO investigations will be granted patents. However, pending patent applications, which have the potential to mature into problem patents, should not be overlooked.

From an FTO perspective, the problem with pending patent applications is two-fold. Firstly, there is always uncertainty as to whether the application will actually result in a granted patent. Secondly, and more problematic, it can be very difficult to predict what the eventual scope of any granted patent will be, as this is not only dictated by the state of the art, but by the commercial aims of the applicant.

If an FTO investigation identifies problematic IPRs, then consideration needs to be given as to how the proposed commercial activities can be pursued while avoiding infringement. One possible reaction to the identification of a problematic third party IPRs is to challenge its validity in an attempt to “clear the path”. In general, achieving a favourable final outcome as quickly as possible, and in the most cost-effective manner possible, will be the main objective.

Post-grant challenges to the validity of patents (for example in opposition proceedings at the EPO, or in national proceedings before a patent office or national court) are typically costly, and can take a long time. What is more, the decisions in these proceedings are often the subject of an appeal, which increases costs further and ultimately leads to a delay in reaching a final outcome.

In the case of pending patent applications, one possible approach is to monitor their progress and to make use of suitable post-grant proceedings if a patent is granted with problematic claims. However, it appears that third parties are increasingly seeking to challenge patent applications while they are still pending, with a view to resolving any potential problems at an early stage and in an attempt to avoid the need for time-consuming and costly post-grant proceedings.

Many patent offices around the world allow third parties to file observations on pending patent applications. Figures from the EPO suggest that comparatively large numbers of observations are filed against applications relating to pharmaceuticals, basic chemicals, medical equipment, special purpose machinery, and measuring instruments. Interestingly, applications relating to electronic technology (e.g. electronic components) seem not to attract very many observations.

Here we discuss the TPO systems of the EPO, WIPO and UKIPO.

TPOs – to file or not to file?

Filing TPOs can provide a cost-effective and straightforward opportunity for a third party to bring relevant prior art to an examiner’s attention (often anonymously), and to provide comments as to why the prior art should be considered relevant. In certain jurisdictions (such as Europe), third parties may also submit commentary on other requirements, including sufficiency, added matter, unity and clarity. In the case of clarity and unity, pre-grant TPOs may be the only opportunity to raise objections, since it may not be possible to raise such issues after grant (these are not grounds for opposition at the EPO, for example). TPOs can also be an effective mechanism to bring prior art to the attention of the applicant, so that it then has an obligation to disclose that prior art in certain other jurisdictions, notably the US.

Notwithstanding the potential advantages of filing TPOs, there are also disadvantages. An obvious disadvantage is that the third party does not itself become a party to proceedings, and so does not have an opportunity to further argue its case (although there is generally nothing to stop a third party filing a further set of observations). In general, the inability of the third party to fully participate in proceedings means that TPOs are at their most attractive where there is highly relevant prior art and the observations can be kept relatively simple; they may be a less attractive option where complex arguments are required.

Of course, another possible downside to filing TPOs is that the applicant is alerted to any potential issues at a stage of proceedings where it has the most flexibility to make rectifying amendments to the application. Thus, an applicant may end up with a “stronger” patent that is more difficult to attack in post-grant proceedings. In addition, the mere act of alerting an applicant to the fact that its patent application is of interest to a third party may encourage the applicant to take steps that may not be favourable to the third party; such steps might include continuing with an application that it may otherwise have allowed to lapse, filing divisional applications, and proceeding with the application in a greater number of jurisdictions.

Although an ideal outcome of filing TPOs is that the patent application never proceeds to grant, an equally effective outcome may result if the applicant is forced to amend the claims so that they no longer represent a problem. Some particularly effective observations are specifically crafted to steer the application towards a particular claim scope that is of no concern to the third party.

Statistics on the effectiveness of TPOs in influencing the outcome of examination are not readily available. However, when filed in appropriate circumstances, we have often found filing TPOs to be an effective tool. For example, in some cases (notably at the EPO), we have even seen our observations adopted in their entirety within examination reports, and significant claim amendments have resulted, largely in the third party’s favour.

TPOs at the EPO

There are essentially two ways in which a third party can seek to challenge a patent application filed at the EPO. The first possibility is to file an opposition within nine months of a European patent being granted. The other possibility is to file TPOs; this may be done at any time prior to the grant of a patent, or even after grant if EPO proceedings are on-going (for example, in the form of opposition or appeal proceedings). In all cases, the third party can act anonymously (although in the case of opposition, a “straw man” must be named).

In Europe, the ability to file post-grant oppositions is generally viewed as an attractive option for third parties seeking to invalidate a European patent. This is because a decision in opposition proceedings has effect in all EPC member states. Approximately 5% of all granted European patents are opposed. Only around 30% of opposed patents survive in the form in which they were originally granted, with the remainder being subject either to amendment or complete revocation.

The cost of opposing a granted European patent is generally seen by large organisations as relatively affordable, especially when compared to the cost of separate post-grant proceedings in multiple national forums across Europe (currently the only option available after expiry of the opposition period at the EPO). Typically ranging from €10,000 to €50,000 once attorney fees have been factored in, these same opposition costs can put off many small and medium sized entities.

In the most recent Annual Report of the EPO, the duration of the opposition procedure – from the date of expiry of the opposition period to the date of the opposition decision – was estimated to be 25.5 months. This period of uncertainty is undesirable for a third party looking to clear the path. Furthermore, it is rare for both parties to the opposition proceedings to be content with the decision of the Opposition Division. As a result, these decisions are often appealed, which significantly extends the period of uncertainty; it is not uncommon for an appeal to take several years. Also, appeal proceedings at the EPO tend to be more costly than opposition proceedings, not only for the parties involved, but for the EPO as well. In 2012, it was estimated that the average cost to the EPO of hearing an appeal was €31,000, while the appeal fee is currently only €1,860.

While it has been possible to file TPOs against European patent applications for over 20 years, in 2011 the EPO introduced measures allowing TPOs to be filed online. The main driver for introducing an online form was the EPO’s “Raising the Bar” initiative, which sought to improve the quality of granted European patents, and presumably reduce the number of oppositions filed. The online form was designed to encourage concise and well-reasoned observations, which can be quickly understood and evaluated by examiners. Another recent development in favour of third parties is that applications on which TPOs have been filed will be examined under the EPO’s PACE scheme for accelerated prosecution, as long as the identity of the third party is given. (It is not currently clear whether the requirement for identification could be met by naming a straw man.)

According to EPO data, the number of TPOs filed increased year-on-year from 2003 to 2013 (Fig. 1). The 53% increase in the number of observations filed between 2011 and 2013 could well be a direct result of the new measures enabling observations to be filed online. It could also be a sign that, during this period, commercial entities increasingly turned to TPOs as a cheaper alternative to post-grant proceedings in an austere climate, and/or a sign of growing frustration at the length of time taken to reach a final decision in opposition and appeal proceedings.

According to other data from the EPO, applications relating to pharmaceuticals make up approximately 17% of all applications that have had TPOs filed against them, while accounting for only around 4.5% of European patent applications filed. Pharmaceuticals are also the most active field for EPO oppositions, according to a 2013 study by Aalt van de Kuilen. This is perhaps not surprising given the commercial value that may be attached to a patent in this field and considering the commercial interests of the generics industry.

At the EPO, TPOs must be filed in writing in English, French or German, and include a statement setting out why the application does not meet the requirements of patentability (or other requirement of the EPC). Because the EPO does not inform the third party of the outcome of its observations, it is advisable to set up a register alert so that any developments are quickly brought to the attention of the third party.

The filing of TPOs with the EPO does not preclude the same arguments being put forward in post-grant proceedings. However, if the observations relate to added subject matter, careful consideration should be given as to whether it is appropriate to file the observations pre-grant as doing so may provide the applicant an opportunity to remove the added subject matter before grant, which might not have been possible post-grant due to the prohibition to extending the scope of granted claims.

TPOs relating to PCT applications

Since mid-2012, it has been possible to file TPOs against international (i.e. PCT) applications. Any observations filed against an international application will be transmitted to the designated (or elected) offices 30 months after the priority date. As a result, third parties can take advantage of this centralised procedure to have a single set of submissions brought to the attention of the applicant, the relevant international authorities and national/regional phase patent offices.

Another advantage of this system (at least in theory) is that it provides third parties with a mechanism to place their observations on file in jurisdictions which do not themselves allow TPOs to be filed.

At the time of writing, TPOs have only been filed on 503 international applications. Given that 205,300 international applications were filed in 2013 alone, the number of TPOs filed so far has to be seen as small.

One of the reasons for this apparent lack of popularity could be the manner in which observations must be filed. TPOs must be made through ePCT public services, which requires the use of a WIPO account (although it should be noted that it is still possible to file anonymously). The regulations only allow the use of a maximum of 5,000 characters to describe the relevance of each citation (up to a maximum of 10 citations), thereby allowing only very short, simple arguments to be made. Moreover, it is only possible to comment on novelty and inventive step at present. Third parties may therefore prefer to wait until national/regional phase proceedings before submitting more detailed observations.

As in most jurisdictions, there is no official fee for filing TPOs. However, unlike in Europe, a third party may only submit a single observation against any particular application, and once one is made it cannot be retracted or modified (although it is hard to see how the filing of multiple observations could be precluded in practice, as long as they are filed using different WIPO accounts). Another condition set by WIPO is that an upper limit of 10 observations may be filed per international application, although it appears that this limit has not been reached to date.

TPOs may be submitted at any time after the date of publication of the international application and before the expiration of 28 months from the priority date. In reality, this gives a 10-month window within which third parties may file their observations. It is, however, recommended to file them as soon as possible after the publication of the application so that they have the greatest chance of being considered before the relevant authority draws up the International Search Report.

Observations may be filed in any language of international publication. However, the International Bureau does not provide translations of the observations to relevant international authorities or to the designated (or elected) offices. If a third party has the option of filing in several languages, WIPO recommends to select the language most likely to allow the observations to be understood by the applicant and by the patent offices in the jurisdictions of interest. WIPO also notes that, in most cases, it will probably be most effective to enter the observations either in English or, in cases where the international application may be undergoing international preliminary examination, in the language of publication of the international application.

From a practical point of view, it is advisable to indicate exactly which claims are considered to be lacking novelty and/or inventive step in view of the disclosure in the cited document, and to submit copies of any citations referred to in the observations. This way, the observations are more likely to be taken into account.

Of the 503 international applications that have had TPOs filed against them, approximately 63% were published in English. Almost a fifth of applications of against which TPOs were filed were for pharmaceutical inventions. Apparently, no TPOs have been filed against international applications whose language of publication is Chinese, Japanese or Korean.

TPOs on GB national patent applications

There is no post-grant opposition system in the UK. However, third parties have been able to make (optionally anonymous) observations against pending GB patent applications ever since The Patents Act 1977 entered into force. In 2005, the UKIPO increased the ease by which third parties can make observations by allowing them to be submitted using electronic media.

Examination of GB national patent applications generally proceeds quite quickly, and so it is generally advisable to file any TPOs sooner rather than later. In order to be considered by the Examiner, it is generally necessary for TPOs to be received before the application has been found to comply with the requirements of the Patents Act.

Like in Europe, observations may be filed on any aspect of patentability or other requirement of the Patents Act. If received in time, UK examiners are obliged take any observations on novelty and inventive step into account, regardless of whether they are reasoned or not.

A tactical tool to pre-empt problematic patents

TPOs represent one of the only ways to challenge a patent application before grant, and thus represent an important tool for IP professionals. While there have been improvements made to the procedure for filing TPOs against EP, PCT and GB applications in recent years, the frequency with which TPOs are filed remains relatively low. However, at the EPO, where anecdotal evidence suggests TPOs can be an effective tool for influencing the outcome of examinations, the volume of observations being filed appears to be increasing rapidly.