In the UK, intellectual property (IP) rights are generally protected as a civil law matter through litigation in the civil courts. Common remedies available to those who successfully enforce their IP at trial include, amongst others, the confiscation of any goods held to infringe the IP in question, injunctions against continuance of any infringing acts, and financial compensation for commercial damage or lost profits.

Nevertheless, in some circumstances IP infringement in the UK may also be covered by criminal sanctions in addition to the usual civil remedies. For example, in the case of trade marks, it is an offence to take unfair advantage of a registered trade mark by applying it to goods without the owner’s permission [1], a sanction that is aimed at the prevention of counterfeiting, and justified on the grounds of protecting consumers. In the case of copyright, it is an offence to deal with unauthorised copies of copyrighted works [2], which, given the ease of illegal online file-sharing, is justified on the grounds of protecting the revenue streams of artists in the creative industries.

However, not all IP rights provide criminal penalties for matters of infringement. For example, in the case of patents, patent infringement itself is not a crime. This is a deliberate omission in patent law, and one that is designed to foster innovation by enabling companies to research and build upon each other’s ideas without worrying about criminal prosecution. To underline the importance of creating the right conditions for innovation, where the Patents Act does prescribe a criminal offence, this is limited to the misrepresentation of a patent having been applied for or obtained in relation to an invention [3]. This tries to prevent companies from unduly ‘pretending’ their inventions are protected and thus stifling innovation.

It is clear, therefore, that there is some division between the need to criminalise IP infringement and the need to foster the right environment for the generation of new ideas and products. Caught between these two seemingly opposing worlds is the field of industrial designs. Designs are often seen as a relatively complex form of IP, and are protected under a number of different legal regimes that sit side-by-side. Principally these different regimes break down into registered designs, which must be applied for at the UK Intellectual Property Office, and unregistered designs, which arise automatically upon the creation or publication of a new design. In the case of registered designs, since the introduction of the Intellectual Property Act 2014 it has been a criminal offence to intentionally copy a registered design in the course of trade. However, there is no corresponding criminal sanction for intentional copying of unregistered designs.

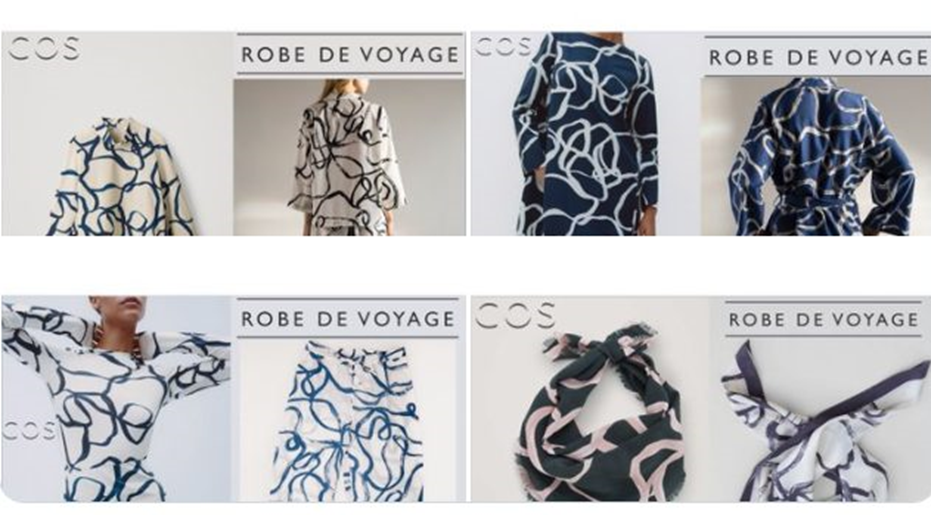

The pressure group Anti-Copying In Design (ACID) lobbied for the introduction of the criminal offence for intentional copying of registered designs and is currently campaigning to introduce a corresponding offence for unregistered designs. In a recent address to the Westminster Media Forum on 8th April 2022, ACID co-founder Dids Macdonald drew attention to a recent dispute concerning fashion designer Jess Linklater of Robe de Voyage, who identified designs very similar to her own for sale by international fashion retailer COS and applied to a range of clothing articles. Ms Linklater contacted ACID, and following ACID’s involvement and considerable social media pressure, COS were brought to the negotiating table and a settlement reached.

Comparison: Robe De Voyage vs COS (Taken from ACID Website)

The details of the settlement remain secret, although it is clear that no admission of liability was made. With no registered design rights to rely on, during the negotiations Ms Linklater will only have been able to rely on unregistered rights. However, it is likely that COS would have been aware of the difficulties that the holders of unregistered rights often face during enforcement actions, and therefore the threat of any possible injunction from Ms Linklater becoming a reality might have been viewed as relatively small one. Moreover, COS may have believed that, due to its size, it would have the resources to outspend Ms Linklater in any legal action. Accordingly, in ‘David vs Goliath’ type disputes, there is an argument that civil remedies alone do not provide an adequate deterrent against infringement of unregistered design rights.

The questions raised over the deterrent value of unregistered design rights is particularly interesting given the importance of design-based industries to the UK economy. According to a 2020 report by the UK Intellectual Property Office, the value-added output to the UK economy attributable to registered designs alone is £79.7bn (without taking into account the additional contribution of unregistered rights), which is the same amount attributable to patents. Furthermore, according to a 2015 study by the Design Council, in the UK around 600 thousand people are directly employed by the design industry, whilst a further 1 million designers are employed across the economy in non-design industries. Ensuring designers have confidence in the protection they are afforded is therefore of clear economic importance.

ACID argues that the situation faced by designers such as Ms Linklater is unfair when compared to the corresponding situation in copyright law. For example, if instead of an item of clothing the product concerned was a literary, dramatic or musical work, such as for example a book, film, or song, the actions of a person who copied and distributed the work would amount to a criminal offence. However, copyright holders have benefited from many years of co-ordinated lobbying on behalf of well-resourced copyright holders, for example in the entertainment industry, who have sought to make the sanctions for copyright infringement a more effective deterrent. By contrast, the design sector is largely composed of small and medium sized enterprises who comparatively lack resources, making a change in law more difficult for these companies to achieve.

Given that the sanctions available under copyright are tougher than those available for unregistered designs, designers may be forgiven for thinking that they could rely on copyright rather than design right to protect their products. However, unfortunately for designers, copyright law contains a provision that makes copyright effectively unavailable for many designs [4]. Therefore, designers who do not intend to register their rights should be aware that in most circumstances only unregistered design rights will be available, and that these rights do not provide criminal sanctions for infringement.

The above differences between the registered and unregistered regimes in design law illustrate the importance of taking a mixed approach to IP protection that does not rely solely on unregistered rights. Not only do registered designs provide criminal sanctions as a deterrent against intentional copying, but, to catch infringement, they do not even require proof of copying at all. Accordingly, registered designs are generally easier to enforce, as has been illustrated in recent decisions in which corresponding claims under unregistered rights have been denied, for example [Rothy’s v Geisswein]. Often small and medium sized companies are put off by the cost of applying for registered designs. However the costs involved are modest in comparison to other rights such as patents or trade marks and certainly much cheaper than litigation. Designers would therefore be well advised to ensure that their portfolios are adequately covered by a mixture of registered and unregistered protection.

At Marks & Clerk, our international team of designs experts understand the pressures faced by designers, and seek to ensure that our clients are able to make the most out of the protections available to them in the sometimes-complex field of industrial designs. If you have a design and would like to speak to one of our experts, please do not hesitate to get in touch.

References

[1] s.92 Trade Marks Act 1994

[2] s.107 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

[3] s.110-111 Patents Act 1977

[4] s.51 Designs, Patents and Copyright Act 1988