The EU’s highest court has ruled that copyright protection can apply to a product whose shape is functional and original. With private vehicle purchases at an all-time low, the CJEU’s ruling in Brompton Bicycle Ltd v Chedech/Get2Get may be exactly what the manufacturing and automotive industries want to hear.

The decision clarifies the extent to which so-called culmination, or overlap, of intellectual property rights is possible under EU law. The recent case of Cofefel confirmed that products could benefit from both design and copyright protection in certain situations and clarified that only originality is required. Brompton now confirms that copyright can subsist in functional objects where the author is free to make some creative choices, akin to the law for Registered and Unregistered designs in the EU. Due to the longer term of copyright, this may be seen as good news for designers in the manufacturing industry and beyond as it may be possible to extend protection in addition to that provided by existing patent and design rights.

Background

British bicycle manufacturer Brompton is well known for its iconic folding bicycle, which was first marketed in its current design in 1987. Brompton had a related patent. However, the maximum term of a patent is 20 years, so this expired in 1999. Registered Community designs subsist for a maximum of 25 years so this would not have been a viable option for Brompton to protect its bicycle appearance today and design rights cannot protect features dictated solely by technical function.

Registered trade marks, which can last indefinitely, are the Holy Grail for many brands. In principal, European trade mark law protect shapes that are distinctive and which indicate trade source to consumers. However, as Jaguar Land Rover found in a recent case, it is not possible to obtain trade mark protection where a product’s shape is exclusively dictated by its technical function, echoing the requirements for copyright and designs. Trade mark protection can also be refused on other grounds, such as where the shape adds substantial value to the goods. These issues highlight an issue with iconic designs that continue to be commercially viable for many decades. Given that many products take several years to make it to market, the duration of consumer-facing protection can be limited.

Perhaps due to these practical considerations, when Korean rival Get2Get introduced a folding bicycle with a similar appearance, Brompton brought a claim in the Companies Court in Liège, Belgium, alleging copyright infringement. It sought an order that Get2Get cease its infringing activities and withdraw its product from sale. This reflects the importance of its intellectual property to Brompton, whose CEO has predicted that electric bicycles will have as big an impact on people’s lives as the introduction of the smartphone.

Get2Get argued in its defence that the appearance of its bicycles was dictated by the technical solution sought and that the appearance could be only protected under patent law, not copyright law. Brompton said that there were other folding bicycles on the market that had different appearances and that as such, their own bicycle, which demonstrated creative choices and originality, should benefit from copyright protection.

The Belgian court found that the shape of Brompton’s famous folding bicycle was necessary to achieve the technical result of being a bicycle that could be unfolded, ridden and folded again. However, it asked the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) to clarify the extent to which EU copyright law protects objects whose shape is dictated by technical function, and the factors to be considered.

CJEU’s judgment

The CJEU has now held EU law does not, in principle, exclude from copyright protection works whose shape is necessary to achieve a technical result. On the contrary, copyright protection can apply “to a product whose shape is, at least in part, necessary to obtain a technical result, where that product is an original work resulting from intellectual creation, in that, through that shape, its author expresses his creative ability in an original manner by making free and creative choices in such a way that that shape reflects his personality”. Shapes dictated solely by technical function will not be protectable by copyright. However, it will be for the national courts in each case to verify whether the designer or author has, in choosing the shape of the product, expressed their creativity ability in an original manner by making free and creative choices and by designing the product in a way that reflects their personality.

The CJEU also confirmed that the intention of the alleged infringer is irrelevant in making such an assessment, a point that differs from the Advocate General’s earlier recommendation. Factors that are external and subsequent to the creation of the product, including related patent rights, are irrelevant.

The Dutch court that referred the case to the CJEU for clarification will now make a decision on the facts about whether the shape of the Brompton bicycle can benefit from copyright protection.

Commentary

The limited term of patents and registered designs and non-applicability of trade marks (and in some cases copyright) represent an issue that has been encountered by manufacturers with particularly long-lived designs. Jaguar Land Rover sought to protect the shape of various Land Rover models. In particular, the Defender models were in production for some 32 years and mostly unchanged thus no longer eligible for patent or registered design protection.

The decision also highlights the extra issues that culmination rights cause for manufacturers seeking to utilise expired intellectual property rights. Get2Get were aware of the expired patent for the Brompton folding design. A patent provides a time-limited monopoly right in exchange for making the information public. However, consideration needs to be given as to what additional rights may subsist when using the knowledge from a patent, especially when there is some creative freedom in how the technical features are implemented.

It will be interesting to see whether UK courts follow a similar approach after Brexit. Although EU copyright law has been subject to much harmonisation, UK courts have often taken a divergent approach. Historically, UK law held that a work was original for copyright purposes if its author exercised skill, labour, effort and judgment and had not copied another work. However, following Infopaq, originality in the EU means that the work originates from or is the intellectual creation of the author. Some previous UK copyright cases, such as a controversial case involving the design of Star Wars Stormtrooper helmets, have also not been favourable to manufacturers of functional designs. In the longer term, will the UK revert to a more segregated attitude to different intellectual property rights, diverging from the EU’s increasingly cumulative approach? Although it provides many challenges, Brexit may give the UK an opportunity to rethink how best copyright can assist innovators in the future.

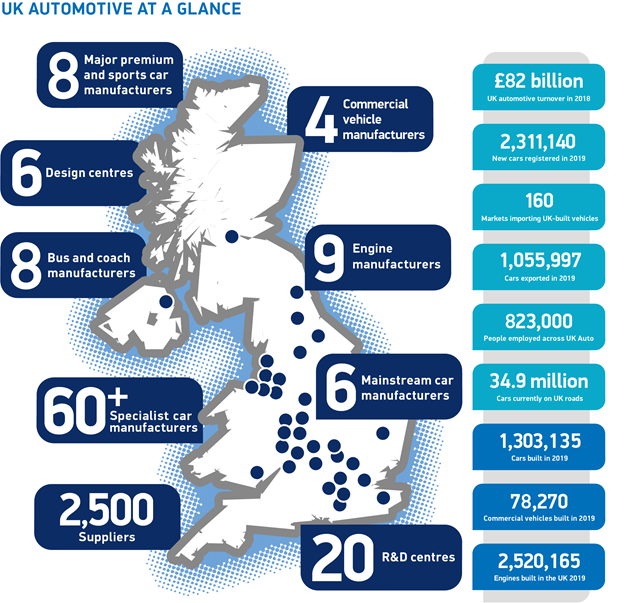

The decision may be welcomed in particular by manufacturers, including those in the struggling automotive and transport sectors. According to trade association The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), the UK automotive industry is worth more than £82 billion in turnover, adding £18.6 billion value to the UK economy. 14.4% of total UK exports are in the automotive industry, worth £44 billion, and the UK is known for its strong technical and design skills, with iconic British car designs from the Mini to the Landrover Defender and the Rolls-Royce Corniche / Bentley Continental.

Source: SMMT

However, with decreasing sales across the industry, environmental concerns and Covid-19 disrupting supply chains and consumer behaviour, budgets are tight. The world’s largest car parts supplier, Bosch, recently told the Financial Times that the industry is facing a huge auto recession that will be worse than the 2008 financial crisis. Manufacturers will want to get more years of protection out of their present designs, where possible, and it may be desirable to explore the possibility of longer-term copyright protection for those that are original works that are not exclusively dictated by technical function. Unlike patents and designs, subsistence of copyright is determined at the point of enforcement and requires copying. Nevertheless, the clarity now provided regarding the protection conferred might embolden designers and manufacturers during a time of significant technological development, as autonomous vehicles provide opportunities for the shapes of vehicles and their interiors to be completely rethought.